On a corner of 26th of July Street in Zamalek, the scent of frying taameya hits first — broad beans, coriander, and cumin rising from a pan of hot oil. The sound comes next: the rhythm of metal spatulas, the thump of bread on wood, the murmur of Cairo’s morning rush. It’s the sound of the city waking up.

Inside, beneath fluorescent lights and tiled walls painted turquoise and orange, a group of young cooks move in practiced chaos. They don’t shout; they dance. Orders slide across the counter — ful with olive oil, taameya extra crispy, shakshouka, eggs with pastrami. Behind the counter, a small framed photo of an older woman watches over them.

Her name is Um Khaled, one of Zooba’s first cooks. She used to make foul sandwiches in Downtown before the founders recruited her in 2012. When asked why she joined a startup instead of staying at her stall, she said, “Because they wanted to make our food famous.”

Thirteen years later, Zooba has done exactly that.

1. The City That Built a Brand

Cairo is a city of eaters. It eats between traffic lights, between shifts, between prayers. Street food is not a cuisine here — it’s an instinct. When Chris Khalifa, a business graduate with a background in finance, and Chef Moustafa El Refaey, a restless young chef obsessed with heritage flavors, met in 2011, they both wanted to answer a simple question: Why isn’t Egyptian food respected abroad?

At the time, fast-casual concepts were sweeping the world — Chipotle, Shake Shack, Five Guys — each elevating local comfort food into global experiences. Egypt had nothing comparable. “We had amazing food,” recalls Khalifa, “but it was hidden behind plastic chairs and fluorescent lights.”

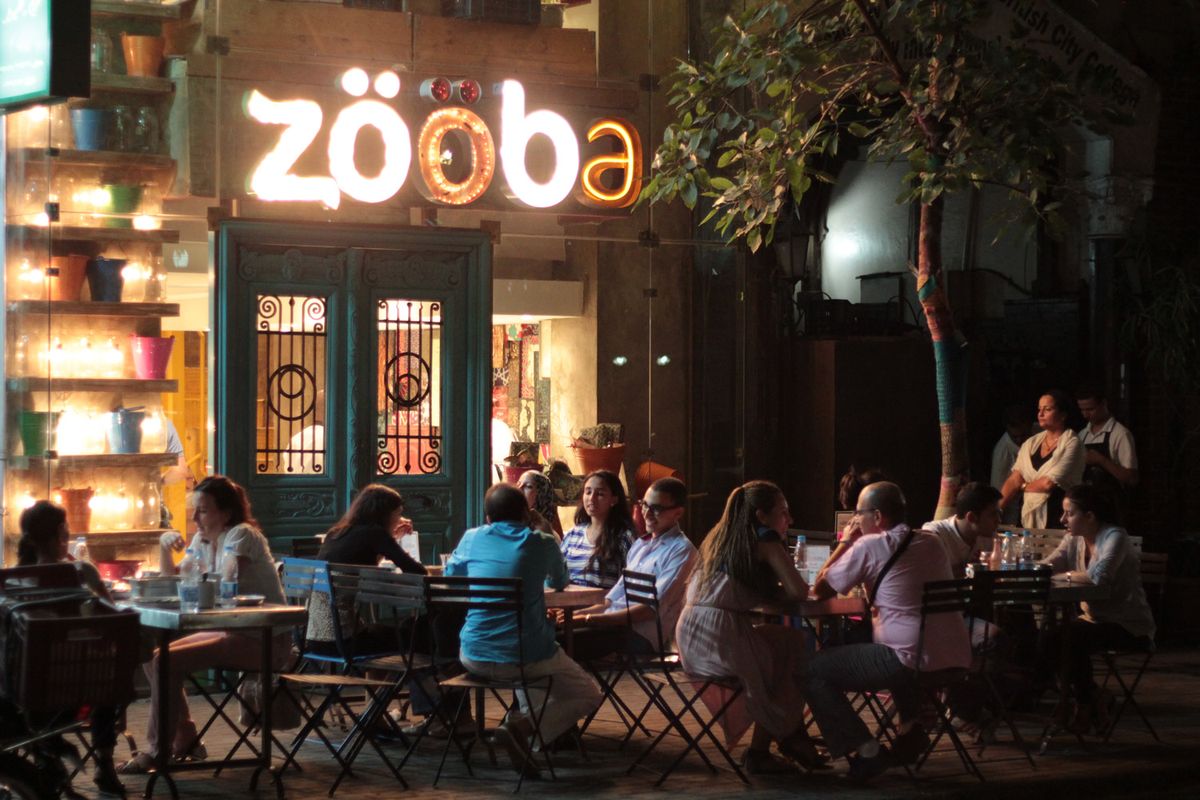

So they built Zooba — a place that treated street food with dignity, design, and data. Named after the Egyptian slang for “a fun get-together,” the brand opened its first branch in Zamalek in 2012, right after the revolution. “The timing was poetic,” says El Refaey. “The whole country wanted to rediscover itself — so did we.”

2. The Revolution in a Sandwich

The first menu was simple: foul, taameya, koshari, beid bel basturma, hawawshi, and fresh juices. But everything — from the typography on the paper wraps to the lighting fixtures — was designed to feel familiar yet new.

“We wanted people to see themselves reflected,” says Khalifa. “Egyptians deserve design. They deserve pride.”

The branding, created by local agency Cairo Ad School alumni led by Ahmed El Sheikh, reimagined the colors of Egyptian street culture: taxi yellow, canal blue, tuk-tuk red. Even the bread was redesigned — baladi, but smaller, crispier, handheld.

In the beginning, locals didn’t know what to make of it. “People would ask, why should I pay 15 pounds for taameya when I can get it for five?” El Refaey remembers. “And we’d tell them: because you’re not just paying for food — you’re paying for a story.”

That story resonated. Within months, Zooba became a fixture for Cairo’s creative class — architects, musicians, designers, and expats. The open kitchen turned cooking into theater; the playlist switched between Umm Kulthum and indie rock. “It felt like home,” says Amira El Adl, a photographer who spent most mornings there editing photos. “You could sit alone and still feel like you belonged.”

3. A Brand Born in Crisis

Building a food brand in post-revolution Cairo wasn’t glamorous. Inflation, supply shortages, and political unrest made every day unpredictable. Khalifa jokes that the real business model was “controlled chaos.”

Yet, somehow, that chaos became part of the brand’s DNA. “Egypt taught us improvisation,” says El Refaey. “If you can run a restaurant here, you can run it anywhere.”

The founders invested in training, standardization, and — perhaps most radically — dignity. Every staff member, from kitchen porter to cashier, received English classes and customer-service training. “We wanted everyone to feel they were part of something bigger,” Khalifa says.

One morning, when the electricity cut out mid-service, the cooks lit candles and kept working. Customers stayed. Someone played a guitar. That day, Zooba sold out before noon.

4. From Zamalek to the World

In 2019, Zooba opened its first international branch in New York City, in Nolita — a neighborhood where rent alone could fund an entire restaurant in Cairo. The move seemed audacious. “Everyone told us Egyptian food wouldn’t translate,” says Khalifa. “They said it was too messy, too specific.”

They were wrong.

The opening drew lines around the block. The New York Times called it “Egyptian comfort food with swagger.” Eater listed it among the city’s best new openings. The restaurant’s glass facade framed a neon falafel logo glowing over Arabic calligraphy — an image that instantly went viral.

Inside, Egyptian cooks worked alongside New Yorkers, shouting orders in a mix of Arabic and English. When a customer mispronounced taameya, a server smiled and gently corrected him: “Say it like this — taa-me-ya. Now you’re part of the family.”

“That’s what we wanted,” says El Refaey. “Not just to sell food, but to teach language, culture, pride.”

Soon after, branches followed in Riyadh, Dubai, and North Coast Egypt, each tailored subtly to local tastes but anchored in the same philosophy: bright design, clean energy, and Cairo attitude.

5. The People Behind the Counter

For all its expansion, Zooba’s soul remains in its people. Many of its staff have been there since day one. Hossam, a line cook from Imbaba, remembers his first week vividly. “I used to sell sandwiches in the street,” he says. “When I started here, they gave me a uniform and said, you’re a chef now. It changed my life.”

Another employee, Nermeen, who began as a cleaner, is now a shift supervisor at the City Stars branch. “They told me: if you can handle a rush at Zooba, you can handle anything,” she laughs. “They were right.”

Even the brand’s HR philosophy became a point of study at the American University in Cairo, where professors cite Zooba as a case study in “socially driven entrepreneurship.”

“We’re not a charity,” Khalifa emphasizes. “We’re a business that believes profit and purpose can coexist.”

6. Reinventing the Egyptian Table

Beyond branding, Zooba’s true revolution lies in its treatment of Egyptian cuisine. Every dish is researched, tested, and retested. “We start with how it was cooked 50 years ago,” says El Refaey. “Then we ask — what does it need today?”

Their taameya recipe uses a proprietary blend of broad beans and herbs; their foul is slow-cooked overnight to preserve texture. Even the pickles are made in-house, in small batches.

Yet the menu is not static. In 2023, they introduced a vegan hawawshi using mushrooms and lentils — an idea inspired by customers during a Cairo Design Week collaboration. “People underestimate how creative Egyptians are with scarcity,” says El Refaey. “We’ve always known how to make something out of nothing.”

At the Zooba commissary in Obour City, where ingredients for all branches are prepped, a whiteboard lists suppliers: Fayoum Farms, Siwa Salt, Minya Herbs. “We wanted to rebuild trust in local sourcing,” Khalifa says. “Egyptian products deserve respect.”

7. The Culture Factory

Zooba doesn’t just sell food; it exports Cairo’s attitude. Its walls are covered with pop art, Arabic graffiti, and hand-drawn maps of the city. Each branch becomes a cultural installation — a playful love letter to the streets that shaped it.

The music, too, is distinctly Egyptian: a playlist that swings from Abdel Halim to Cairokee to Wust El Balad. “We wanted people abroad to hear Cairo,” Khalifa explains. “The energy, the imperfection, the humor.”

Even the packaging speaks. Each paper wrap carries a phrase in Arabic and English — el akl 3ala el mashy (food on the go), made with love and tahini, or ya salam 3ala el zooba! It’s branding that laughs with you, not at you.

8. The Global Stage

Zooba’s success abroad sparked a quiet wave of Egyptian pride. For years, local cuisine had been overshadowed by regional powerhouses — Lebanese, Turkish, Moroccan. Now, Egyptian food had a global flagship.

In 2022, Zooba participated in Dubai’s Taste Festival, serving over 12,000 dishes in three days. In 2023, they catered an event at the United Nations Headquarters during Egypt’s COP27 presentation, introducing diplomats to koshari and ful. “It wasn’t just catering,” says Khalifa. “It was diplomacy through flavor.”

Later that year, Zooba New York was featured on Netflix’s “Street Food: Middle East” — where Chef Moustafa shared how Egypt’s culinary identity had survived colonization, globalization, and crisis. “We’re a nation of improvisers,” he told the camera. “We turn leftovers into art.”

9. The Critics and the Copycats

With success came criticism. Some accused Zooba of gentrifying street food, of packaging poverty into aesthetics. Masoud, the chef we featured earlier, once commented at a panel: “The danger isn’t commercialization — it’s forgetting the people who invented it.”

Khalifa doesn’t deny it. “That’s why we always give credit,” he says. “Our recipes come from real people — street vendors, home cooks, grandmothers. We visit them, learn from them, pay them. Zooba isn’t an appropriation; it’s a collaboration.”

Other brands soon followed — boutique koshari shops, gourmet hawawshi trucks, artisan foul pop-ups. “Competition is healthy,” says El Refaey. “It means Egyptian food is finally trending — and trending is the first step to belonging.”

10. Homecoming

Despite global fame, Zooba’s Cairo kitchens remain the heartbeat of the brand. On any given morning, the Zamalek branch still buzzes with familiar faces — artists with sketchbooks, taxi drivers grabbing breakfast, office workers laughing over tea.

When asked if he ever dreams of a Michelin star, El Refaey shakes his head.

“My Michelin moment is when a cab driver walks in, tastes his sandwich, and says, ‘da akl betna’ — that’s our food.”

Last Ramadan, Zooba partnered with local NGOs to deliver 10,000 meals across informal neighborhoods. “We don’t post about it much,” Khalifa says. “Some things are sacred.”

11. Beyond Food: A Mirror for Cairo

Zooba’s story mirrors Cairo itself — improvised, vibrant, and impossible to categorize. It’s not fine dining or fast food; it’s a hybrid of hustle and art.

At the end of the day, what Zooba sells is not sandwiches. It sells a feeling — the comfort of the familiar, dressed in dignity. It’s the taste of home, plated for the world.

In the Zamalek kitchen, the morning rush fades into afternoon calm. The team wipes counters, hums to the radio. A child outside presses his face to the window, pointing at the taameya sizzling in the oil. The cook smiles, flips one, and waves.

“Every Egyptian has a Zooba story,” Khalifa says. “That’s how I know we’ve done something right.”