The following is an analysis of the website's methodology and a re-imagining of the provided text, crafted to mirror the distinct voice and style of People of Cairo.

Analysis of People of Cairo (Methodology & Insights)

Based on an analysis of the site's content—specifically articles like "Why Cairo Never Sleeps" and "The Square That Lives Inside Us"—the writing style of People of Cairo is defined by a specific set of characteristics:

- The "Nomadic" Observer: The narrator often adopts the persona of a wandering philosopher—someone deeply embedded in the city’s chaos yet capable of stepping back to see the soul of it. The voice is collective ("we," "us," "our streets"), creating an immediate bond with the reader.

- Romantic Realism: The writing doesn't shy away from Cairo's grit—the traffic, the noise, the struggle—but it frames these elements as essential to the city's character. It finds beauty in the mess.

- Elevated Prose: The language is literary, often using metaphors (e.g., "Alchemists of Garbage," "Eternal Second Wind"). It avoids dry reporting in favor of storytelling that evokes mood and atmosphere.

- Cultural Deep-Dives: Topics are never just surface-level news; they are deconstructed to explore why they matter to the Egyptian psyche. A story about clinics isn't just about healthcare; it's about our collective anxiety, our escapism, and our changing identity.

- Structure: Articles typically begin with a philosophical hook or a sensory-rich scene, move into the core subject matter (woven with social commentary), and conclude with a reflective, often open-ended thought on the future of the society.

Rephrased Article

Title: The Quietest Noise in Cairo: Why We Are Finally Talk About the Screens That Stole UsCategory: Lifestyle / SocietyReading Time: 12 Minutes

If you stand on the corner of any major street in Cairo—let’s say, in the crushing hum of Downtown or the sleepless arteries of Nasr City—you are surrounded by a very specific kind of noise. It is the noise of life asserting itself. The microbus horns speaking their own secret language, the vendor calling out the sweetness of his potatoes, the overlapping conversations of a million people trying to make it to tomorrow.

We have always prided ourselves on this noise. We wear our chaos like a badge of honor. We are the city that never sleeps, the people of the eternal second wind, the culture that lives out loud.

But lately, if you look closely, underneath the cacophony of the streets, a different kind of silence has settled in. It is a silence that sits at dinner tables where no one is speaking. It is a silence in the cafes where friends sit together, bodies present, but minds drifting somewhere in the blue light of a handheld universe. It is the silence of a generation that has learned to live, fight, love, and escape through a sheet of glass.

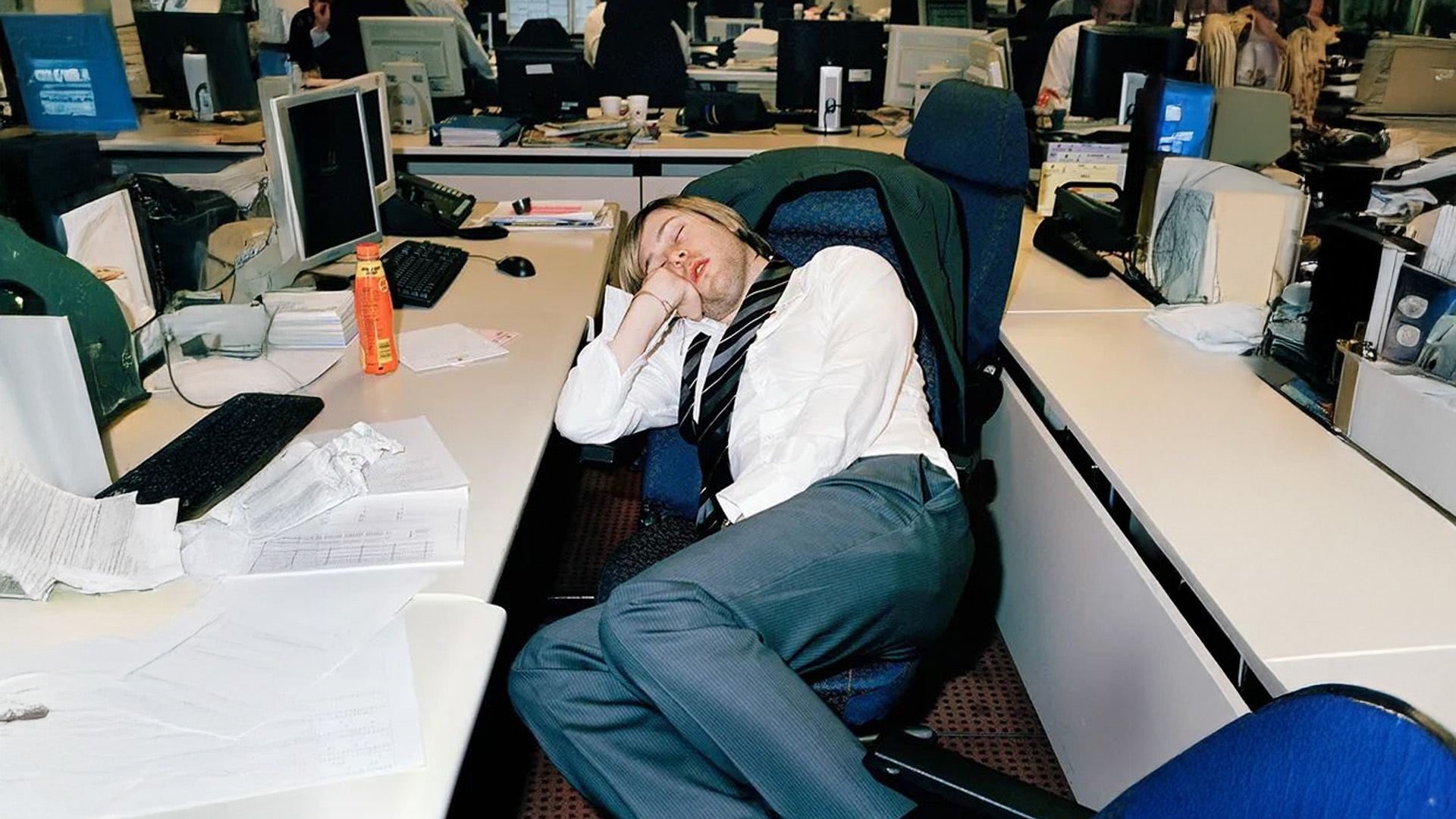

For a long time, we treated this shift as a joke. We laughed about the "zombie" teenagers or the husband who checks his notifications before he kisses his wife good morning. We called it "modern life." We called it "passing time."

But somewhere between the endless scroll of TikTok and the dopamine loops of late-night gaming, the screen stopped being a tool. It became a place. And for too many of us, it became the only place that made sense.

This week, for the first time, the Egyptian state officially acknowledged what every mother, teacher, and partner has felt in their gut for years: This is not just a habit. This is not just "kids being kids." This is a fracture in our reality.

The Ministry of Health and Population has launched a quiet revolution—specialized clinics for internet and gaming addiction across six psychiatric hospitals. It is a move that is as startling as it is necessary. It is an admission that in our rush to modernize, to connect, to digitize, we may have lost the ability to simply be.

The Sanctuary of the Screen

To understand why this initiative matters, you have to understand why we retreat in the first place.

Cairo is not an easy city. We know this. It demands a piece of you every time you step out the door. The traffic demands your patience; the economy demands your anxiety; the social expectations demand your conformity. In a world that feels increasingly out of control, the digital world offers the ultimate sedative: Control.

Inside a game, effort is directly rewarded with progress. If you grind for ten hours, you level up. In real life, you can grind for ten years and still feel stuck in the same place.On social media, you curate the version of yourself you wish you were. You are not the tired employee squeezed onto the Metro; you are the witty observer, the aesthetic traveler, the success story.

The screen became our refuge. It became the place where we went to numb the noise of the "Real."

But the refuge has turned into a prison.

We see it in the university student who hasn't attended a lecture in weeks because the anxiety of leaving his room—and his console—is physically paralyzing. We see it in the young woman who feels a phantom vibration in her pocket every three minutes, her cortisol spiking at the thought of missing a digital interaction that will be forgotten in an hour.

We see it in the silence.

A Diagnosis, Not a Judgment

The launch of the "Your Health Is Happiness" initiative is significant not just because of the services it offers, but because of the language it uses.

In Egypt, the word "addiction" (Idman) carries a heavy, rusted weight. We reserve it for the dark corners of society. We reserve it for heroin, for tramadol, for the things that destroy families in dramatic, visible ways. To apply that word to a smartphone—an object that is as essential to our lives as electricity—feels almost insulting to some.

“He’s not an addict, he’s just smart with computers.”“She’s not dependent, she just has a lot of online friends.”

We rationalize it. But the Ministry’s new clinics are cutting through the denial with clinical precision. They are operating out of six major hubs: Al Abbassia in Cairo, Al Khanka in Qalyubia, Al Maamoura in Alexandria, Damira in Dakahlia, and hospitals in Minya and Assiut.

The message is geographic and symbolic: This is happening everywhere. From the coastal north to the Upper Egyptian south, the screen does not discriminate. It does not check your ID. It does not care if you are a CEO or a high school student.

The clinics are introducing a treatment model that feels radically compassionate for a public health system that is often overwhelmed. The process begins not with a lecture, but with a question. The "Internet Addiction Questionnaire" is not designed to shame the patient; it is designed to map the architecture of their dependence.

How many hours? What happens when the Wi-Fi cuts out—do you feel bored, or do you feel panic? Has the digital world cost you a relationship? A job? A grade?

It is an approach that treats the patient not as a moral failure, but as a human being caught in a loop designed by some of the smartest engineers in Silicon Valley to keep them trapped.

The Architecture of Care

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of this initiative is the "Safe Hours" protocol.

In a culture that often swings between extremes—total permissiveness or authoritarian banning—this approach offers a middle path. The clinicians are not suggesting we smash our routers. They are not suggesting a return to the Stone Age. They know that technology is the spine of modern Egypt.

Instead, the program focuses on "renegotiating the terms of surrender."

The concept of Safe Hours is about reclaiming time. It is about carving out lucid moments in the day where the screen is dark, and the human is awake. It is about relearning the lost art of boredom.

Remember boredom? That uncomfortable, itching feeling that used to force us to daydream, to pick up a book, to walk to a friend's house unannounced? We have cured boredom with infinite content, but we have lost creativity in the process.

The clinics are staffed by 120 specialists who have undergone rigorous training. This detail is crucial. In the past, a teenager complaining of gaming addiction might have been dismissed by a traditional doctor with a laugh and a "just grow up."Now, they are met with professionals who understand the neurochemistry of dopamine loops. They understand that for a 15-year-old, the loss of an online community is a genuine grief. They are trained to listen, not to dismiss.

The People Behind the Pixels

Let’s imagine the people who will walk through these doors.

There is the mother in Maadi, watching her eight-year-old throw a violent tantrum because the iPad was taken away for dinner. She is scared, not just of the behavior, but of the realization that she doesn't know how to calm him without it.

There is the twenty-something freelancer in Dokki, whose entire career and social life exist on Instagram. She looks successful to the world, but inside, she is hollowed out by the constant performance, unable to sleep without the blue light bathing her face, terrified of the silence of her own thoughts.

There is the father in Assiut who realizes he hasn't looked his son in the eye for a continuous five minutes in a year.

These are not "cases." They are us.

The initiative acknowledges that digital addiction manifests differently across generations, but the root is always the same: a displacement of life. The clinics are offering a way back. They are offering integrated treatment plans that include psychological support, family counseling, and behavioral therapy.

But beyond the clinical walls, the Ministry is launching a digital awareness campaign—fighting fire with fire. They are using the very platforms that enslave us to offer us a key to the handcuffs. The National Platform for Mental Health is now hosting self-assessment tools, normalizing the conversation, making it okay to ask: “Am I in control, or is this thing controlling me?”

A Return to the Physical

There is a profound irony in writing this article online, to be read by you, likely on a screen. We are all complicit. We are all part of the ecosystem.

But this initiative marks a turning point in the Egyptian consciousness. It is a declaration that while the digital world is a part of life, it cannot be life itself.

We are a culture built on physical presence. We are the culture of the ahwa, where chairs are pulled close and tea is spilled and arguments are had face-to-face. We are the culture of the grand family gathering, of the crowded wedding, of the handshake that lasts a little too long.

When we trade that for a comment section, we lose something fundamental to our DNA.

The clinics in Abbassia, Khanka, and Maamoura are not magic wands. They will not unplug Egypt overnight. They will not stop the tide of algorithms designed to monetize our attention span.

But they are a start. They are a lighthouse in the digital fog.

They are telling us that it is okay to put the phone down. That the world will not disappear if you look away for an hour. That the anxiety you feel when you disconnect is not a sign that you need more screen time—it is a sign that you need to reconnect with the messy, loud, tangible reality of your life.

For the first time, the system is saying: We see you.

We see the struggle behind the closed bedroom door. We see the exhaustion behind the glowing eyes. And we are here to help you find your way back to the surface.

In a city that never stops moving, this might be the most important movement of all—the movement to stop, to look up, and to finally see each other again.